With the ever-growing power of social media, more companies are shelling out increasing amounts of cash to advertise on sites like Facebook and Twitter. According to Bloomberg, social-media-ad spending is expected to reach a total of $4.8 billion at the end of 2012 and $9.8 billion by 2016.

While there is a shift underway in the advertising world from investing money in TV spots and magazine ads to purchasing Facebook’s sponsored stories and Twitter’s sponsored tweets, one thing remains the same across different marketing mediums: the use of celebrities to push products. It’s a tactic that has been around for decades (does anyone remember those over-the-top Cindy Crawford Pepsi commercials from the ’90s?), and one that is being recycled and reinvented for our current digitally saturated society.

There is solid evidence that suggests that celebrity endorsements (both compensated and uncompensated) can skyrocket a product from relative obscurity to nationwide recognition. The Oprah Effect is probably the best-known example of celebrity-induced rise to commercial fame. Oprah is so influential that she has a Midas-like touch: any product she mentions on her show or bills as one of her “Favorite Things” and any book she selects for her book club gain the attention of millions. Just like some YouTube videos, these products go viral. People want them, think that they need them, and buy them. When Oprah selected Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina for her book club in 2004, the 19th-century novel reached #1 on USA Today’s Best-Selling Books list. After Oprah featured the book lights and magnifiers from LightWedge on a December 2007 episode, the company website, which previously averaged $3,700 in sales per day, made $90,000 in sales in a single afternoon.

New Time, New Tweet

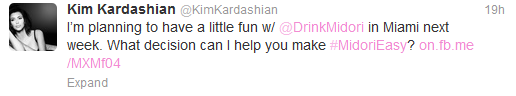

Oprah isn’t the only celebrity with commercial clout, hence the inability to watch a TV show without seeing at least one celebrity-endorsed ad. But with the millions of people on Twitter, companies now believe they cannot survive on media and print ads alone. It’s a new time in the advertising world. Enter, the sponsored tweet. Celebs (I use that term loosely, because some of the people who send out sponsored tweets are reality stars) broadcast their support for products through tweets like these:

To marketers and advertisers, these stars have two things that make them the perfect product pushers: influence and thousands (sometimes millions) of followers.

Companies who solicit celebs to tweet on behalf of their products believe in the “to make money you have to spend money” philosophy. And spend money they do a lot of it. These sponsored tweets are not cheap, especially tweets sent out by celebs with a high follower count. According to Vulture, Snoop Dogg makes $8,000 for a single tweet; Kim Kardashian gets paid $10,000, and Charlie Sheen collected a $50,000 per tweet when he plugged Internships.com.

The tweet by Busy Phillips advertising Bacardi appeared on my timeline recently and prompted me to start thinking about the effectiveness of sponsored tweets. Companies spend thousands of dollars banking on the fact that people will take commercial advice from actors, singers, athletes, and reality stars and model their consumer behavior on that of their favorite stars. They hope that we will be influenced by those who are influential.

Sponsors, Skepticism, Tweets, and Trust

I think there is a problem with this philosophy. I’m suspicious of sponsored tweets, because there is no proof that the celebrity actually uses the product he/she tweets about. When a celebrity is featured on a TV commercial, we are presented with an image of that celebrity using whatever product they are endorsing. Emma Stone appears in commercials for Revlon lipstick, which show her using said lipstick. Regardless of whether she actually uses Revlon products, it looks like she does. When Carrie Underwood appears in ads for Biore, she is actually using Biore face wash. The same goes for other products that feature recognizable faces in their commercials: Neutrogena, Garnier, Olay, to name a few. Yes, appearance often diverges from reality, and these celebrities probably earn a paycheck announcing their love for something they don’t even use, but an image is a powerful thing.

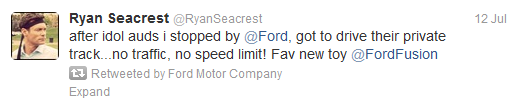

With Twitter, oftentimes there is not this visual component. Sometimes a tweet may link to an ad where a celebrity is pictured with the endorsed product (as is the case in the Kim Kardashian tweet above), but I would argue that there is a difference between a picture of Kim Kardashian holding a bottle of Midori and a commercial that shows Sarah Jessica Parker actually changing her hair color from blonde to brunette with Garnier Fructis before our very eyes. Consider the Ryan Seacrest tweet. I’m unsure of whether this is actually a paid tweet (though it doesn’t really matter, because Seacrest is the emcee of Ford’s new social media marketing campaign, and I’m assuming he’s being compensated for that), but it’s hard to believe that Ryan Seacrest, whose net worth is $75 million, would actually use a Ford Fusion.

But, if I’m leery and skeptical when it comes to sponsored tweets, why would companies use them? We follow celebrities we admire, so maybe companies think that if we support a particular person, we will also support that person’s products. This leads me to ask, do celebrity-endorsed tweets work? Are people that impressionable? Will they buy or use something because a celebrity promotes it?

Theories of Influence

Malcolm Gladwell

Companies who pay celebs to tweet for them subscribe to the Malcolm Gladwell theory of influence. Gladwell, author of The Tipping Point, proposed a theory called “The Last of the Few”, which says that a small group of people with massive followings influence our purchasing decisions and behavior. These few powerful, influential people are “gatekeepers”; they impact the choices the rest of us make and thereby have the power to set trends into motion.

Ed Keller and Jon Berry put forth a similar idea in the book The Influentials. According to Keller and Berry, one in every ten Americans is an influential, meaning that they have sway over society because people seek out their ideas, thoughts, and opinions. People want to know what these influentials think, so they follow the examples set by influentials. Again, they have the ability to impact the behavior and opinions of society. Case in point: the Oprah Effect.

What does this mean from a marketing and advertising perspective? Following the logic of Gladwell, Keller, and Berry, if a company wants to influence society, they should target the small yet powerful group of influentials. They should reach for the top tier: get to the authoritative individuals and reach others through them. According to this theory, sponsored tweets make perfect sense. If reality stars and athletes tweet an endorsement about a product, they will inspire other people to buy that product. Ultimately, a trend will begin, and that product will gain societal name recognition, all because of one incredibly powerful person. That person is a medium through which products pass from marketers and advertisers to consumers. The key in the path from tweet to trend is a well-known person with a substantial following. Effectively targeting that type of person is what successful viral campaigns are made of.

Duncan Watts

Yet, it’s not quite that simple. Duncan Watts challenges the theories of Gladwell. A Fast Company article articulately sums up Watt’s ideas: Watts says that popularity can be attributed not to a small, omnipotent group of individuals but rather to the “pass-around power of everyday people”. It’s small, intimate sharing that spreads content: ordinary people sharing with friends and family. Also, according to Watts, a trend’s success does not depend on the person who starts the trend. It depends on how susceptible society is to the trend. Sure, there’s always one person who sparks a trend, but Watts says that person steps into the role unintentionally; he/she is an “accidental Influential.”

Watts also proposes that the reason behind success might be random. When a song reaches the top of the charts or a clothing brand overtakes America, it’s not entirely because the song or brand is high-quality. Part of popularity is chance.

So, if content is spread by everyday people, and success is partially random, then advertisers not only have to predict how receptive society will be to a specific product/person/service, but they also have to market to a large audience. Watts acknowledges that certain people are more influential than others, but the problem that advertisers face is that they never really know who will cause a trend to take off. So, they can’t just target a cadre of the commercially powerful; they have to reach a broad consumer base.

If Gladwell’s theory is music to advertisers’ ears, then Watts’ arguments sound cacophonous and unharmonious. Watts clips the wings of the Twitter bird and makes the efforts of all those businesses that buy into (pun intended) sponsored tweets seem useless. Marketers may want to believe that Gladwell is right, but can they?

Who’s Right?

The Case for Gladwell

In answering the question of whether sponsored tweets work, I turned to research.

- According to the responses to Charlie Sheen’s tweet about Internships.com, Gladwell is #winning when it comes to the battle of influence theories.

Within one hour, this tweet generated 95,333 clicks. It ultimately reached 181 different countries, and Internships.com received 74,000 applications in response to Sheen’s tweet.

- I also found a study by Anita Elberse and Jeroen Verleun entitled “The Economic Value of Celebrity Endorsements”, which focuses on the way in which endorsements by professional athletes affect sales and stock returns. The study doesn’t examine sponsored tweets in particular, but I think it offers some interesting insights into celeb endorsements in general. Elberse and Verleun found that a company’s decision to use an athlete endorser generally had a positive pay-off. It increases brand-level sales in an absolute sense and relative to the firm’s competitors, suggesting that athletes have a direct impact on consumer purchasing behavior.

The Case for Watts

- A study by BuzzFeed and StumbleUpon published in Ad Age found that data sharing (including data that goes viral) occurs via small groups. Influentials can reach a wide audience through a single Facebook status or tweet, but the impact is short-lived. Content goes viral when it extends beyond those influential people, when ordinary people share with their friends. This study looked at 50 stories that received the most Facebook traffic since mid-2007. Some of these posts had millions of views, but the ratio of views to shares was 9:1: that means that for every Facebook share, only 9 people visited the story. When it comes to Twitter, for every Twitter share, only 5 people visited a story. Because these ratios are so low, in order to get millions of views, you have to reach a lot of people. One celebrity sharing content won’t generate enough views. These 50 popular Facebook stories become popular because of an incredible amount of intimate sharing, the most common outlet for content.

- This study says that content sharing “mirrors the offline world”. To go viral, people need to focus on engaging millions of people with great content rather than on the “risky or impossible task of finding theoretical influentials”.

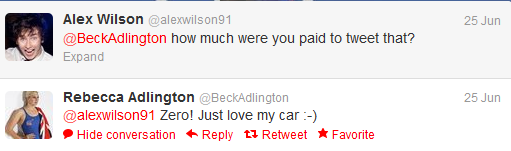

- The phenomenon of word-of-mouth marketing supports Watts’ idea of the “pass-around power of everyday people”. A Nielsen report suggests that individuals buy things not because a celebrity tells them to, but because their family and friends recommend it. People trust those close to them, and even complete strangers. 92% of people trust recommendations from people they know; 70% of people trust consumer opinions posted online. I think the fact that people trust complete strangers on sites like Yelp is extremely interesting. I also think there are two important things to note: one, these people that others deem trustworthy are ordinary, everyday individuals, not celebrities. And, two, said trustworthy people (unlike celebs) are not being paid to recommend products. Money may muddle up the trust factor for many people, causing them to be apprehensive when it comes to celebs who receive big paychecks to plug products. Here’s a great example of some brand-sponsorship suspicion:

Rebecca Adlington may not have been paid for this particular tweet in which she publicized her love for BMW, but she is sponsored by the luxury car company, so she is, at the end of the day, being paid by them.

- A Crowdtap poll suggests that the opinions of family and friends (those intimate sharing circles that Watts talks about) influence people’s purchasing decisions. 70% of people said that they tried a new product because a family member or friend suggested it/posted it online. Again, this proves that trends/products take off because of the conversations and dialogue of everyday people. It also bolsters the theory that marketers must target a wide audience rather than a select group of influentials.

- New research out of St. Joseph’s University suggests that celebrity-sponsored tweets have minimal influence on the opinions of people ages 18-27 when it comes to familiar brands. However, researchers discovered celebrity tweets are an effective tool for lesser-known brands looking to capture the attention of a large audience quickly.

The Big Split

I don’t think there’s a clear winner in the face-off between Gladwell and Watts, because I think that there is convincing evidence for both sides. In the battle between celeb broadcasting and intimate sharing, some people ardently argue on behalf of Gladwell, while others are all about Watts.

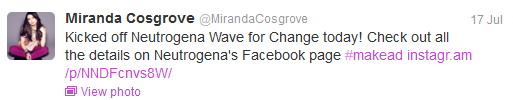

Brands are also split along Gladwell-Watts lines – even brands within the same industry. Consider the skin-care industry. Neutrogena uses celebrities as “ambassadors”; these stars appear in commercials for Neutrogena face washes and tweet on behalf of the brand:

This is a perfect example of a marketing campaign built on the Gladwell philosophy.

Dove, on the other hand, uses the ideas of Watts as the foundation for its advertising efforts. Dove has built its entire campaign on “real women” (and real men). Rather than harnessing star power to sell their skincare line, Dove focuses on everyday people: the consumers who go to the store and purchase Dove products. Women of all ages, ethnicities, and body types appear in Dove commercials, and the brand spotlights men and women on Facebook and Twitter.

When it comes to building ad campaigns around influential theories, it’s different strokes for different folks.

Risky Business

It’s worth noting that celebrity endorsements can be a risky business venture. An article from Forbes sums up the relationship between celebrities and brands:

Whenever a brand elects to align with a celebrity, that celebrity becomes an extension of that brand,” he explains. “That means the beliefs, comments and actions of that celebrity are tied to the brand as well.

Celebs as brand extensions can be a good thing, if a product is endorsed by a celebrity who has a wide fan base, manages to stay scandal free, and is seemingly innocent (Taylor Swift, perhaps?) But, if a star gets into Alec-Baldwin-like antics, then any products he or she backs might suffer. There are numerous examples of celebrity endorsements that were pulled after a star became embroiled in some type of controversy: that of Michael Phelps, Kate Moss, O.J. Simpson, Madonna, Michael Vick, Kobe Bryant, Tiger Woods, Chris Brown. A company can’t predict how a celebrity will act, so is spending millions of dollars and placing part of its fate in human, prone-to-mistakes hands a wise decision?

There’s another problem with stars serving as product pushers. One study found that a celeb’s negative associations can transfer to the product he/she is endorsing. Take Kim Kardashian’s tweet for Midori. Say people have a negative view of Kim K (which I don’t think is too much of a stretch). They will associate her negative traits with Midori liqueur. And they probably won’t buy it. Keeping this study in mind, any celebrity endorsement seems risky because no actor, singer, athlete, and certainly no reality star is perfect. They all have negative characteristics, and there will always be a group of people who aren’t fans and therefore will transfer a celebrity’s flaws to the endorsed product. Maybe the key is selecting a celebrity whose fans outnumber his/her detractors (read: none of the cast members of Jersey Shore).

Non-Endorsement Deals

Sometimes, companies turn the idea of an endorsement deal on its head and pay celebrities to not endorse their products. Abercrombie & Fitch paid Mike “The Situation” Sorrentino (aka that obnoxious yet ripped guy from Jersey Shore) to refrain from wearing the A&F brand. Abercrombie released the following statement:

We are deeply concerned that Mr. Sorrentinos association with our brand could cause significant damage to our image. We understand that the show is for entertainment purposes, but believe this association is contrary to the aspirational nature of our brand.

Can a brand that sells clothes by featuring ads in which models are not wearing clothes really be described as ‘aspirational?’ Also, a clothing company that forces employees to do push-ups and squats when they make mistakes could benefit from an endorsement by The Sitch. How do they think he got that ripped bod? The G in GTL and the push-ups and squats in an A&F store? Seems like a match made in endorsement heaven.